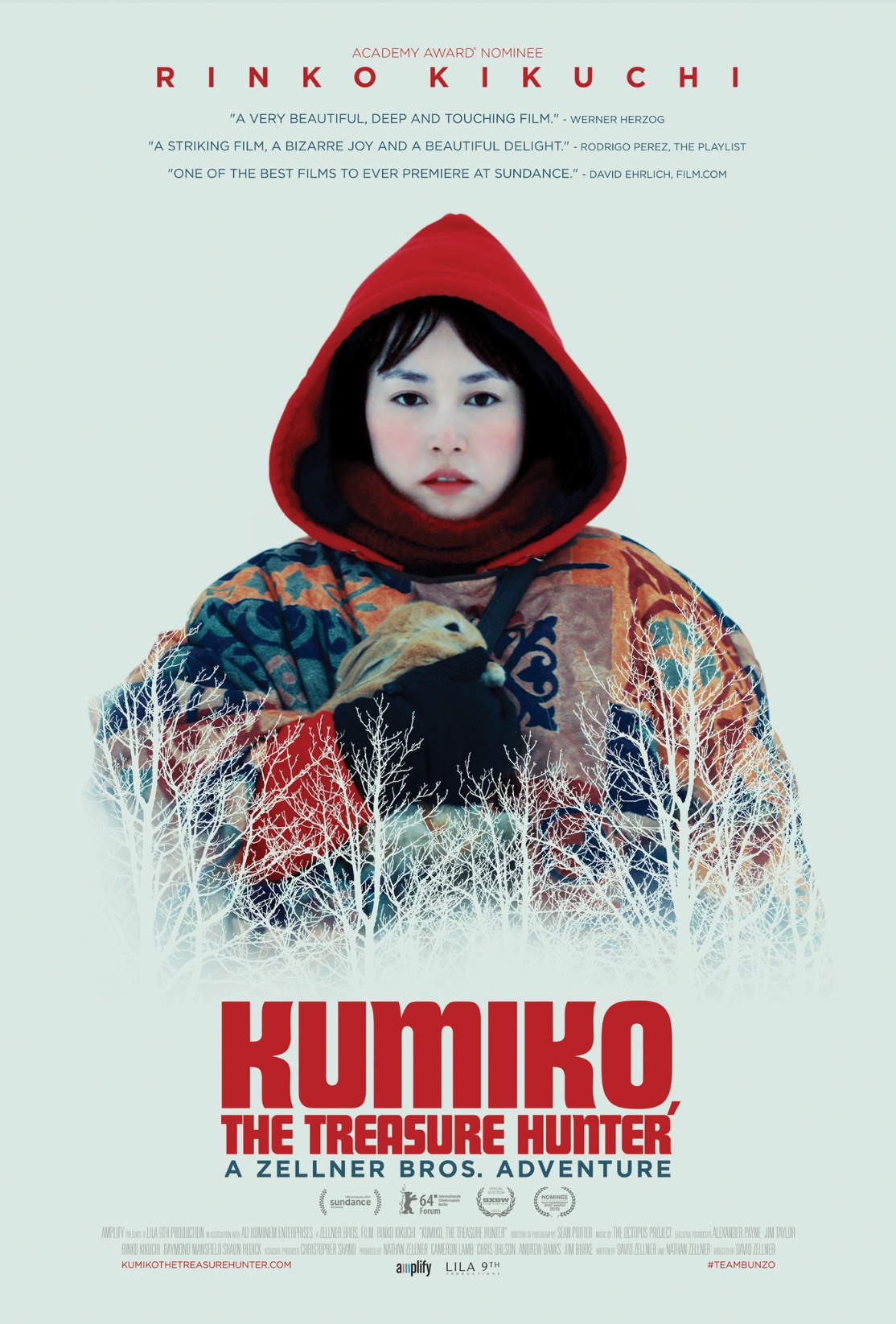

Kumiko the Treasure Hunter

Ralph Hammann

April 18, 2015

On November, 15, 2001, Takako Konishi, a young Japanese woman from Tokyo, was found dead in a field in Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. Although she was a suicide, a misunderstanding with a police officer with whom she had spoken gave birth to the urban legend of a Japanese woman who believed the film, Fargo, to be true and died while trying to find the suitcase of money that Steve Buscemi's character buried in the snow. From this slight tale, the Zellner brothers have fashioned a fully original film that defies easy categorization.

Magic realism, fantasy, dark comedy, surreal quest film, Beckettian road movie -- all are apt descriptions of parts of “Kumiko,” but none quite satisfy in classifying a film that avoids being pigeon-holed with the adeptness of its own gentle brand of cinematic jujitsu. It's also far more than a sympathetic portrait of mental illness as some suggest.

Certainly something is off-balance in the mind of 29 year-old Kumiko, whose only companion is "Bunzo," a charming rabbit, and whose discovery of a VHS tape of Fargo precipitates a monomaniacal journey that is undertaken with a deliberateness and precision that is obsessive, delightful and troubling. When she explains her motives for wanting to steal a world atlas because she needs the map of North Dakota, she tells a library guard that she is like a Spanish Conquistador traveling to the West in search of treasure. That is, perhaps, the first clue as to the great underlying and interlocking themes of the film: the journey west in search of gold, the (vain) pursuit of the American Dream and a twisted version of manifest destiny. It also suggests Don Quixote in search of his impossible dream, at once riddled with pathos and humor.

Sean Porter's cinematography renders every frame of the film exquisite, whether it is the depiction of Kumiko's stultifying life as an "office lady" with her identity stripped away under a black and white uniform — or whether it is Kumiko against a frozen Minnesota landscape in her red hoodie, an iconic image that pokes our collective unconscious. Even shots of airplanes being de-iced take on a folkloric luster, appropriate to enchantment of Kumiko and the start of her physical trip to America.

The timing of the painterly composed shots is masterful, with Zellner knowing just how long an image has a right to stay on the screen, as well as a masterful sense of comic timing. Without any strained stylistics, he manages the whimsical humor that recalls the best efforts of Wes Anderson, Alexander Payne and, yes, the Coen brothers, whose work is eclipsed by "Kumiko."

All of this would be in vain without an actress capable of delivering a nearly silent portrayal of a woman whose depression, alienation and longing are felt in even the smallest gestures, briefest of glances and subtlest of postures. From the very outset of the film as she picks her way along a beach to the ending where she trudges through unforgiving snow, Rinko Kikuchi imbues each figurative and literal step with meaning, determination and poignance. As the oppressed office worker, her body slumps unnaturally inward and outward; when she finds her purpose being denied, a feral intensity flashes through her veins. It's an astonishing emotional workout that keeps one in states of halted breath only to be suddenly rocked with laughter or pierced with sadness, often at the same time. Deftly balanced between comedy and pathos, Kikuchi's phenomenal, raw, committed performance asks for no sympathy, yet is heart-wrenching and haunting.

Fine supporting performances from David Zellner as a befuddled cop and Nathan Zellner as an inept travel agent (both hilariously yet touchingly clueless to the world beyond their frozen heartland), point up the cultural gulf between America and Asia. But it is an encounter with a lonely woman, which trenchantly reveals what has replaced the American Dream in America. When Kumiko insists that she go to Fargo, the woman dismisses the notion and tells her she'll take Kumiko to the Mall of America instead. But Kumiko's dream is much more grand. No mere capitalist, Kumiko is a divinely crazed dreamer like Quixote and Werner Herzog's "Fitzcarraldo," who set their sights on magnificence as opposed to dross trinkets - treasure that can lift them from their unacceptable existences in stasis. Kumiko may be a mad innocent, but she is ennobled by her quest. And while one's first reaction is that she is a victim; further reflection suggests that she is a hero.

This is a very shrewd film about the dream of the West's El Dorado that has been sold for centuries, but never more persuasively than by Hollywood. And, perhaps, never more desired at present than in Asia, where American films have tremendous influence. That Kumiko's dream is based on an exported lie makes the film all the more affecting, upsetting and darkly humorous.