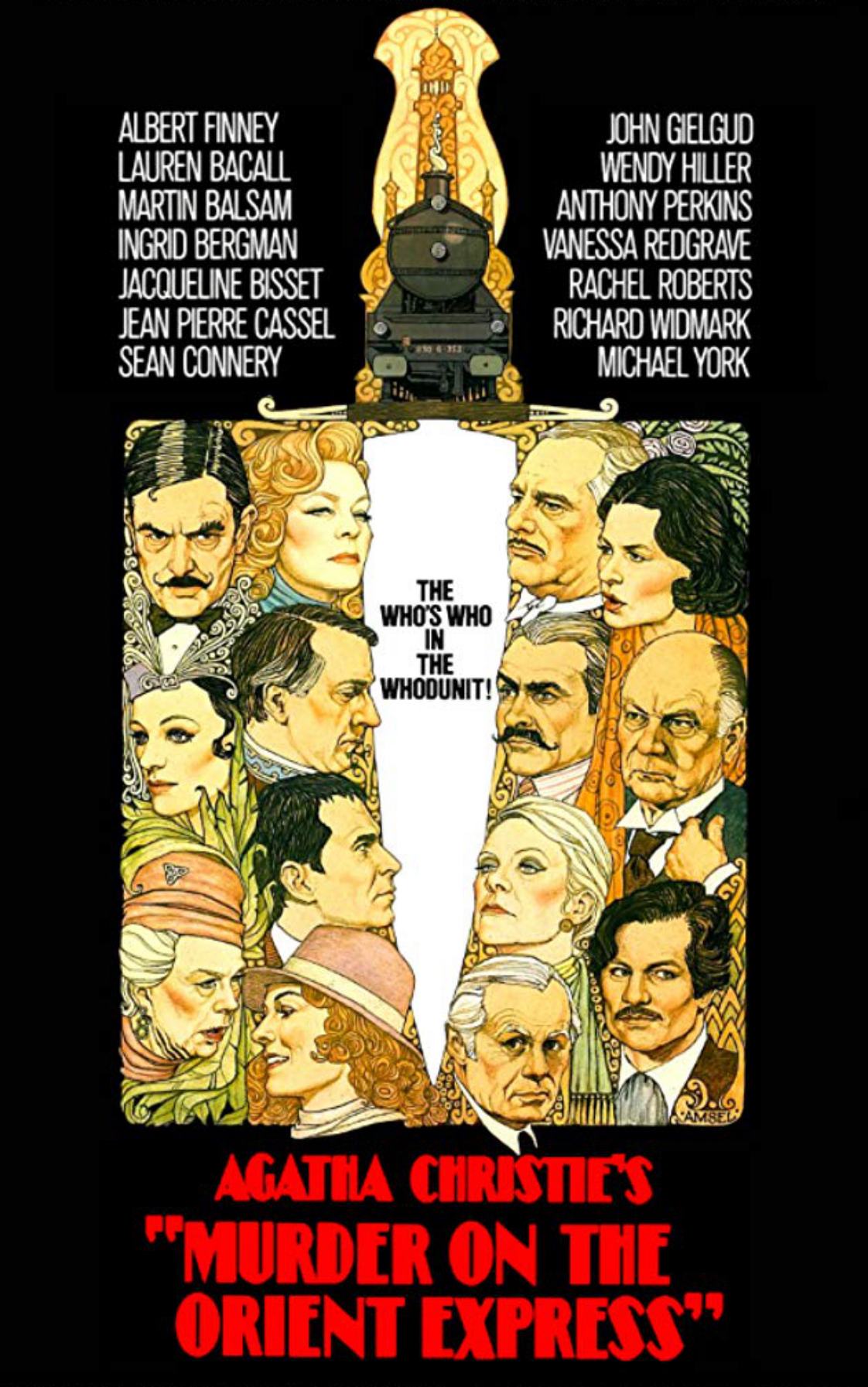

Murder on the Orient Express

Ralph Hammann

November 10, 2017

Had Kenneth Branagh appreciated Sidney Lumet’s version of this Agatha Christie mystery, perhaps he would not have remade it; and that would have been a good thing. Then again, on evidence of his ego, he doubtless would have made it. Nor is there any reason to think that he could have appreciated Lumet’s artistry.

At every turn and climb, Branagh reveals what an inferior director he is of mise-en- scene and what little skill he has in directing actors, action, suspense, plausibility or much else of what is required in a well-constructed piece like that of Christie’s. One suspects that the venture exists as a vanity piece for him to flaunt a caricature of a mustache on the face of an undercooked ham. Apparently Branagh has fantasies of making a series of his Hercule Poirot, a role played with more fidelity and panache by everyone who has preceded him, particularly David Suchet and Albert Finney, whose Poirot in Lumet’s film remains the high mark of the Belgian detective’s cinema appearances.

One hopes Branagh will not be boarding the steamship on the Nile for another Christie outing, as is threatened here. Perhaps by then he might muster up a more convincing, plummy and consistent an accent as Suchet, Finney and Peter Ustinov (the Poirot of 1978 Death on the Nile), but having to suffer through his confrontations with his inner demons as if he is still playing Shakespeare, has no place in Christie. He misses the style most of the time, only conveying Poirot’s eccentricities as appendages as opposed to lived-in habits. The running gag of Poirot asking gentlemen to fix their neckties is neither funny nor earnest and comes across more as a piece of schtick, which must be delivered at regular intervals.

Branagh is only capable of holding his own, but no more, opposite his better co-stars; Finney inveigled the best from his, while never letting anyone forget that he was in full control. As director, Branagh seems to think that the film is solely about Poirot and thus inserts scenes that waste time while doing little to develop the plot or the essential parts of his character. It even takes too long to get aboard the train, as Branagh must first deliberate over eggs and solve a robbery in Jerusalem. And once we arrive at it, there is little to impress. Whereas Lumet managed to turn it into a character as well as setting, here it is only a vehicle.

Where Lumet captivated us in the closed set of the train, Branagh does his best to open matters up and have scenes staged implausibly and laughably out doors. While a crew of workers struggle in heavy clothes to remove snow and put the engine on the tracks (the later, an unnecessary bit), Branagh serves tea to Daisy Ridley outside in the cold with inadequate attire and a full absence of frosty breath. He also walks atop the train (out of character for Poirot) for no reason other than to get an interesting shot, and he stages a bit of ridiculous and unnecessary action on a train trestle out of insecurity that Christie’s plot and the performances are sufficient to hold our interest. Worst, he stages the revelation scene outside with an eye-catching backdrop of train and mountains that is clearly intended to make the climax more

dramatic. It’s too bad he couldn’t have relied on acting and more intimate camera work to do the work. However, so badly has he mismanaged the pieces in Christie’s delectable construction, that it probably couldn’t have built to its requisitely elegant conclusion.

Lumet, who also had is roots in the theater, knew how to explore a theatrical, closed set environment; Branagh only performs in front of various backdrops at key moments. While Lumet makes the unreal real as his camera inhabits the train, Branagh cuts to an X-ray overhead view that draws attention to its contrivance while destroying the illusion of reality that the set designers have tried to accomplish, even if it is a punier reality than the majestic Orient Express designed in by Tony Walton in 1974.

That express was ignited by Geoffrey Unsworth’s shimmering photography and electrified by Anne V. Coates’ editing — and it even had its own theme music, a grand piece by Richard Rodney Bennett, which captured the marvel of the great machine launching into the wilds with as much ceremony as royal ocean liner on her maiden voyage.

Almost everyone in this remake pales after the cast that Lumet assembled and directed with esprit de corps. Worst is Johnny Depp in the role that Richard Widmark made an indelible imprint on without having to resort to a put-on accent and scar appliances. Widmark’s businessman was calculating to the core; Depp’s lacks depth. It’s another collection of tricks that, failing to distract in the service of illusion, only distract.

In his paltry review of the 1974 film, Jay Cocks, with no taste for the epicurean, complained that Lumet’s use of major film stars didn’t work. Utter poppycock. Far from being distractions, these actors were able to imbue their characters with both substance and sufficient charisma to reserve their berths on the elegant ride. Half of Branagh’s riders fail to register either because they lack interest as actors or because Branagh has given them short shrift in order to film himself or the odd bit of aforementioned derring-do.

To be sure, Branagh and his producers are banking on their collection of faces to bring in audiences. It may work, but absent any plot momentum and chemistry, the actors feel less like they are performing in the sort of ensemble nurtured by Lumet, and more like they are getting star turns — and these of highly diminished magnitude.

So, yes, Dame Judy Dench (so overused as dowagers) must bow before Dame Wendy Hiller’s princess; Josh Gad is a sad substitute for Anthony Perkins; Derek Jacobi is not nearly as good as Sir John Gielgud, Penelope Cruz (one of the more earnest performances) isn’t given a chance to make the impact of Ingrid Bergman; Michelle Pfeiffer (another sincere effort) lacks the steel of Lauren Bacall; Leslie Odom, Jr (apparently a token black) and Daisy Ridley lack the command of Sean Connery and Vanessa Redgrave — the rest expire as soon as they are off-camera, unlike their predecessors: Martin Balsom, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Rachel Roberts and Michael York.

Anyone who saw the Lumet film will remember the final flashback that accompanies, without undercutting, Finney’s summation. I won’t spoil it, but suffice to say Lumet allowed each actor a wonderful couple of seconds to summarize his or her motivation in a single gesture. It dazzled and gave one goosebumps and catharsis at once. Branagh bungles it with a jerky camera haphazardly recording the action in murky black and white.

Christie has said that she considered Lumet’s film the best adaptation of any of her works, and she said that Finney came closer than anyone to being her Poirot. Their accomplishments remain unequalled.